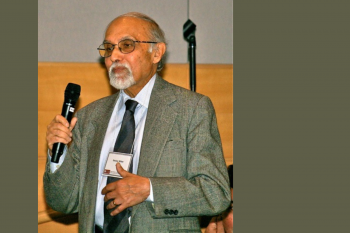

MIT Professor Emeritus (post-tenure) Sanjoy Mitter, a member of the MIT Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, died June 26 at age 89. An expert in the theoretical foundations of systems, communication and control, Mitter contributed to significant engineering applications, most notably in the control of interconnected power systems and pattern recognition.

Sanjoy Mitter was born in 1933 in Calcutta, India, to a prominent family with a distinguished line of jurists. His paternal grandfather, Sir Binod Mitter, was a member of the Judicial Committee of Britain’s Privy Council. His paternal great-grandfather was Sir Ramesh Mitter, the first Indian chief justice of the Calcutta High Court in the 19th century. His maternal grandfather, Sir C. C. Ghose, was a justice of the Calcutta High Court and was several times acting chief justice.

He was born to father Subodh Mitter and mother Protiva Mitter, née Ghose. Subodh Mitter broke with the judicial lineage of his family and went on to become an electrical engineer and industrialist. Sanjoy followed suit, receiving his BS in mathematics in Calcutta in 1954, his BS in electrical engineering from the Imperial College of Science and Technology in London in 1957, and his PhD from the Imperial College of Science and Technology in 1965.

His career began with a four-year stint as a development engineer with Brown Boveri and Co. in Baden, Switzerland, before moving on to the Battelle Memorial Institute in Geneva, followed by Imperial College (where he served as fellow in the Central Electricity Research Board from 1962 to 1965), and then Case Western Reserve University, where he taught from 1965 to 1969 before joining the Department of Electrical Engineering at MIT as a visiting associate professor. He became an associate professor in 1970 and full professor in 1973.

MIT remained Mitter’s home base for the rest of his career, where his most profound and lasting imprints were undoubtedly upon the hundreds, if not thousands, of students, mentees, co-workers, and friends he accumulated during his long and notable career at the Institute. However, his travels extended to multiple sojourns at other universities: He was a professor of mathematics at the Scuola Normale in Pisa, Italy, from 1986 to 1996, and held visiting positions at Imperial College, London; University of Groningen, Holland; INRIA, France; Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, India; ETH, Zürich, Switzerland; and several other American universities and institutions, including the University of California at Berkeley and the Los Alamos National Laboratories.

A true citizen of the world, Mitter was fluent in both French and German as well as English; his first wife, Adriana Mitter Fachini, hailed from Milan, Italy; their marriage lasted until her death in 2008 and sprawled between Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Florence, Italy, where they maintained two homes. Irvin Schick, co-editor with Theordore E. Djaferis of the influential “System Theory, Modeling, and Control: a tribute to Sanjoy Mitter”(Springer Science+Business Media, 2000), wrote in his introduction to the text that “[Sanjoy and Adriana’s] whereabouts at any given time, much like the precise location of subatomic particles, can only be stated probabilistically.”

At MIT, Mitter was founding co-director of the Center for Intelligent Control Systems (CICS), which later merged with the Laboratory for Information and Decision Sciences (LIDS), which today is housed by the MIT Schwarzman College of Computing. Mitter oversaw many foundational advances in the field now broadly referred to as information and decision science, including innovations in communication networks, numerical algorithms for control design and large-scale optimization, nonlinear estimation, statistical signal and image processing, and the newly emerging field of robust control. As co-director of LIDS alongside Robert Gallagher from 1986 to 1999, he saw the lab develop neuro-dynamic programming and contribute to significant advances in coding and information theory, large-scale statistical inference, and estimation.

The animating principle which made CICS (and later LIDS) such hotbeds of innovation was almost certainly the interdisciplinary approach baked into the lab’s structure. Peter Doerschuk ’77, EE ’79, SM ’79, PhD ’85, an electrical and computer engineer at Cornell University, wrote the following in a letter supporting the work of CICS. “I believe that there are three key aspects of [Mitter’s] leadership of the Center: (1) The breadth of vision of what intellectual areas belong in the Center, (2) the willingness to take risk, and (3) the willingness to pursue curiosity-driven activities.”

In a similar letter, Pietro Perona, professor of electrical engineering and of computation and neural systems at Caltech and director of the NSF Engineering Research Center in Neuromorphic Systems Engineering, compared his time at LIDS to a visit to the Renaissance: “The intellectual and social atmosphere that I met in Professor Mitter’s group at LIDS was unique and precious, wholly new to me. I liken it to the atmosphere of the Renaissance court as one could have met in a small city-state such as Urbino and Mantova in the 1500s. At its center, the enlightened prince, Sanjoy Mitter, would provide funding, inspiration, emotional support, and an aesthetic canon. The courtiers — the graduate students and postdocs, all of them absolutely first-rate — would be given the intellectual freedom, the encouragement, and the resources to follow their own curiosity, and encouraged to work on a diverse array of problems (speech, vision, probabilistic representations of geometrical objects, variational problems, handwriting) with the common requirement that that any investigation should be intellectually and analytically rigorous, and aim at the fundamental issues underlying every problem in computational perception…”

Mitter’s interdisciplinary approach to intellectual pursuits was almost certainly informed by his near-encyclopedic memory for papers, books, and other scholarly materials he’d encountered months or even years before, as his advisee Tom Baran, now co-founder and CEO of Fathom Optics, recalls: “Many wonderful conversations with Sanjoy started with him asking something like ‘So, how is progress on your PhD work going?’, and ended with a pad of paper in hand, absolutely filled with references to seek out, the exact authors and exact years of publication all recalled from his memory, going back to the 1970s, 1960s, and earlier.”

Mitter’s uncanny recall was tempered with great personal warmth and a gift for conversation, all of which made him a popular mentor. Paul-Peter Sotiriadis PhD ’02, Electronics Lab director and professor of ECE at the National Technical University of Athens, Greece, paid tribute to Mitter thusly: “I will forever hold Professor Mitter in the highest regard, both as a remarkable scientist and an exceptional human being. His groundbreaking work in mathematical systems and control theory has left an enduring impact. Throughout my time at MIT, his unwavering support, guidance, and inspiring teaching were invaluable to me. I felt honored to have him on my PhD committee.”

Frank Moss SM ’72, PhD ’77, co-founder of Bluefin Labs and former director of the MIT Media Lab, paid tribute to Mitter’s kind nature: “I remember him as the quintessential mannered gentleman, very warm, friendly and collegial, a great conversationalist with a deep intellect and sharp wit. A rarity at MIT at that time, and even now. I ran into him on campus several times when I was director of the Media Lab between 2006 and 2012, nearly 40 years after that. He would greet me with a warm hello as if no time at all had passed.”

Michael Warren ’69, MS ’71, PhD ’74 recalls Mitter’s near-infinite capacity for curiosity: “He was inspirational and always a fine gentleman, as much at ease with discussing economics or politics as he was with discoursing on system theory.” Gordon Kaufman, the Morris A. Adelman Professor of Management Emeritus and professor of statistics emeritus within the MIT Sloan School of Management, agrees, referring to Mitter as “among the last surviving members of a generation of MIT intellectual princes. He was old-school gracious, knew how to listen, and was beloved by his students. We were closest of friends for 50 years, sharing fine wine and gastronomic adventures in France and occasional mathematical moments here in the U.S. Sanjoy was a strategic thinker, one who was not afraid to address big intellectual problems.”

That intellectual fearlessness yielded a body of work which garnered Mitter international acclaim. Among his many awards and honors, Mitter was a fellow of the IEEE and IFAC; was elected to the National Academy of Engineering (1988); won the IEEE Control Systems Award (2000); elected a foreign member of Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti (2003); awarded the AACC Richard E. Bellman Control Heritage Award (2007); received the IEEE Eric E. Sumner Award (2015); and was named a foreign fellow of the Indian National Academy of Engineering (2015).

Following the death of his first wife Adriana, Mitter reconnected with, and married, childhood friend Rekha Ghosh, who survives him. Other members of Mitter’s extended and accomplished family include younger brother Pronob Mitter, niece Anjali Mitter Duva, and nephew Siddhartha Mitter.

Additionally, Mitter is survived by a large network of friends, students, and mentees who considered him akin to family; as news spread of his passing, condolences and personal remembrances arrived from dozens of academic institutions around the globe. “He was Uncle Sanjoy to our children and grandchildren (save the latest, born in May),” recalls Peter Falb, professor emeritus of applied mathematics at Brown University and a LIDS research affiliate, of his 50-plus year friendship with Mitter. “He spent many Thanksgivings, Christmases, birthdays, and visits with our family. While he was, of course, a distinguished colleague, he was primarily a close and dear friend.”

Kaufman agrees, alluding to Mitter’s impact with devastating simplicity: “He made his mark. I will miss him.”