Image Credit

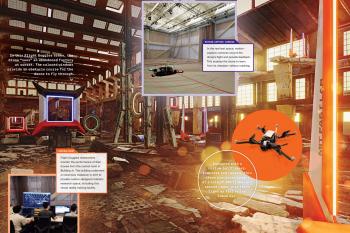

Courtesy of Sertac Karaman (Virtual Interior Building); John Aleman (Drone); Varun Murali (Control Room)December 18, 2019

LIDS professor Sertac Karaman and his team use virtual reality to help reduce drone failure rates.

Christine Thielman I MIT Spectrum (Original article)

Drones go almost everywhere these days, providing access to places too dangerous or remote for people to explore. They support disaster relief efforts and military reconnaissance missions, and they document the impact of climate change by monitoring the intensity of storms, counting endangered wildlife, and photographing beach erosion.

Unfortunately, drones often crash, damaging costly equipment and stalling research, according to Sertac Karaman SM ’09, PhD ’12, associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT. To reduce failure rates, Karaman and his team use virtual reality (VR) to train drones, simulating environments that unmanned vehicles might encounter in the real world. They call this VR training system for drones “Flight Goggles.”

The drones programmed by Karaman and his colleagues “see” a world rendered as if in three dimensions—like a video game. The drone learns how to navigate in this environment without the risk of colliding with physical objects.

In reality, the drone is flying in what looks like a big empty gymnasium—a state-of-the-art testing facility made possible by the 2017 renovation of Building 31, one of MIT’s oldest research buildings. Outmoded workshops and labs were transformed into custom-designed space for research in robotics, autonomous systems, energy storage, turbomachinery, and transportation. The top-to-bottom modernization also added more than 7,000 square feet of usable space for students, faculty, and researchers.

Karaman has lofty goals for his drone technologies; for example, saving more lives in disaster response work. “So many people lose their lives in the first 15 or 20 minutes after a natural disaster,” he points out. “If you could locate them sooner, tell rescuers where they are, you could save more people.”

While the human brain can process an astonishing amount of information, he observes, in an emergency, our split-second decisions are often wrong. “Imagine a system that can make those decisions for you,” Karaman says, noting that autonomous super-vehicles promise to have maneuvering and navigation capabilities that go far beyond today’s human-piloted or human-driven vehicles. “That’s an innovation that will save as many lives as the invention of the seatbelt.”